If you order a takeaway coffee at a café, you will get a plastic cup filled with coffee, a plastic straw and a plastic takeaway bag. In fact, the use of plastic is all too common in our lives as it has many advantages such as a cheap price, easy to produce, and its lightweight. Plastic is known as the miracle material of the 20th century. However, the resulting environmental pollution that comes along with disposing this indestructible material has become a serious problem.

|

| ▲ Micro-plastics being found in bottled water has raised people's awareness towards the problems (Photo from the woked.com) |

Plastic waste does not disintegrate like normal biodegradable trash. It takes hundreds of years for the material to breakdown and decompose. Furthermore, microplastics are being found to compound the problem. Thus, The Dankook Herald (DKH) investigated the growing concerns around microplastic pollution.

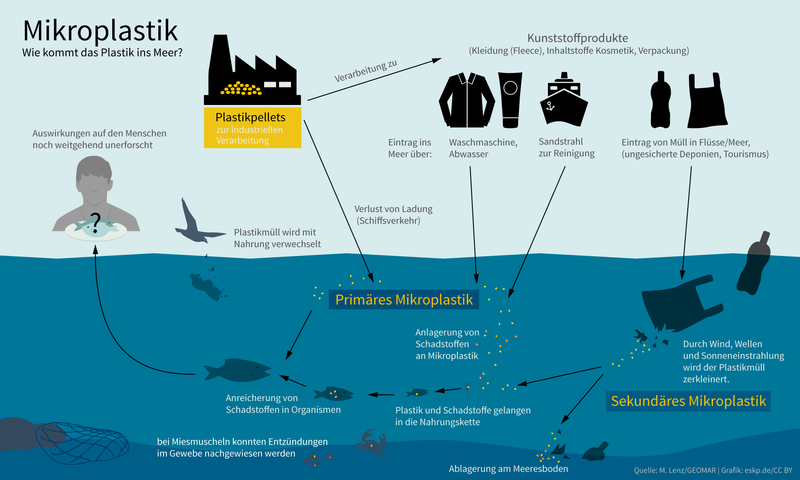

Microplastics can be described as small plastic, less than 5mm, that results from the break up of larger manufactured products or plastic that is simply made small to begin with. According to a 2016 report by the environmental group Greenpeace entitled, “Micro-plastics in the Seafoods that We Eat”, when contact lenses or vinyl waste for instance are dumped into a drain accidently or intentionally, they are broken down into pieces as they go down to the sewer mostly by some micro-organisms. As a result, these particles are not filtered through the purification process and form instead a system of microplastic infiltration of our waterways. These broken down pieces head straight into the ocean or nearby rivers.

|

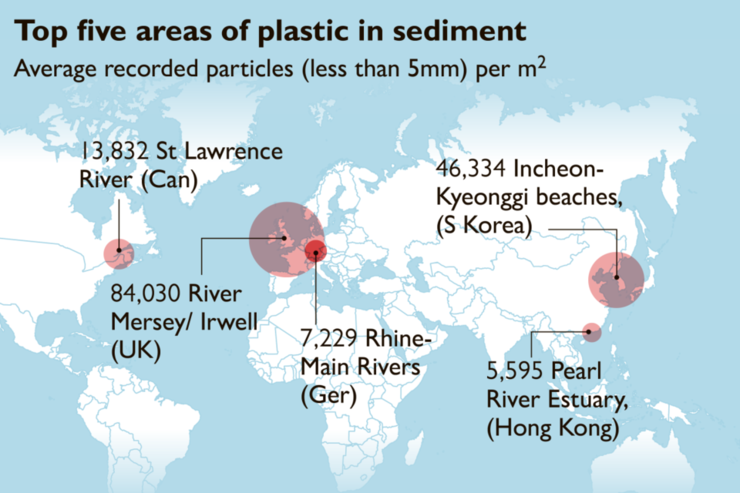

| ▲ Infographic of what causes and effects micro-plastics have on the marine ecosystem.(Photo from the times.co.uk) |

According to Korea’s first study of microplastics by the Korean Ocean Science and Technology Institute, Geoje, South Gyeongsang Province, and the shores of Jinhae, has an average of 550,000 discovered microplastics, the highest concentration in the world. The Korean Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries says that about 30 percent of the plastics that pollute the ocean come from buoys floating in the seas, of which Korean fish farmers use around 50 million. What’s worse, two million of them have even been disposed of at sea. Due to an absence of laws that would force farmers to collect their abandoned buoys and a lack of suitable places to dispose of them, the recovery ratio of abandoned buoys has never exceeded 28% annually.

After seeing the impact of microplastics on the environment, many people wondered if it was bad for humans too. Opinions remain divided. Those who believe microplastics are harmful to the environment insist that they are toxic to humans. As the Greenpeace report pointed out, the problem impacts human when plankton eats microplastics as food. Also, microplastics floating in the ocean tend to absorb toxic chemicals from the sea. If a fish eats these microplastics, it is digesting these toxic chemicals too.

|

| ▲ Micro plastics in our daily life do not disappear when discarded, threatening and destroying the ecosystem.(Photo by wikimedia) |

This same Greenpeace study showed that microbes like DDT and hexachlorobenzene paralyzed the reproductive capacity of many marine creatures in plankton and fish experiments. Therefore, eating fish is very likely to be harmful to humans because of the chemicals they ingest when eating these microplastics. However, to date there have been no specific studies conducted on the impact of microplastics on humans.

It is hard to expect the industry to autonomously expel microplastics in the absence of any actual guidelines or legal precedence both domestically and abroad. Although the Ministry of Environment has put the prevention of the use of microplastics into a 10-year comprehensive plan for environmental health, it has not yet set a clear goal for its abolition and there has yet to be any substantial progress made on this issue.

The establishment of a monitoring supervision system is also very challenging. Regulations relating to the production of cosmetics and household goods are handled by the Food and Drug Administration, but they have yet to table any provisions regarding the use of microplastics. The Food and Drug Administration may review its regulations to account for the use of microplastics, but as of now, there are no clear plans to do so.

As people are becoming more and more concerned about the effects of microplastics, the movement to reduce them is slowly picking up. The United States passed the "Microbead-Free Waters Act" in December 2015. The bill contains a ban on the sale and distribution of ‘rinse-off’ cosmetics products made of petrochemical substances such as polypropylene and polystyrene. This legislation, however, has limitations that does not apply to microbeads found in 'leave in' products such as sunscreen agents. In countries like Taiwan, Canada, Australia, the UK, the Netherlands, Sweden and Belgium, solutions are still being discussed.

There is also an industry-wide movement to expel microbeads. Several global companies have already pledged to phase out the use of microbeads. For instance, L'Oréal and Procter & Gamble have opted to discontinue the use of polyethylene microbeads by the end of 2017. However, many companies have been unable to escape the criticism that they are being too passive on this matter. In some cases, the scope of the microplastics they use is vague and narrowly defined, or the products impacted by the commitment to remove microbeads are limited.

Korea's cosmetics industry is also aware of the problem of microbeads. In April 2016, the Korean Cosmetics Association recommended that its manufacturers voluntarily stop using microbeads by July 2017 to "prevent environmental pollution." AMOREPACIFIC and LG Healthcare promised to stop using them in their products. This is pretty significant given that these two companies accounted for 61.8% of the domestic cosmetics and household goods market in 2015.

NGOs and related organizations are also rallying to stop the use of microplastics. There are currently a few non-profit organizations fighting for this cause including, Plastic Pollution Coalition, 5Gyres, Fauna & Flora International, The Marine Conservation Society, The Environmental Investigation Agency, Story of Stuff, The Plastic Soup Foundation and Plastic Free Seas. Furthermore, ‘Beat the Microbeads Foundation’, a coalition of 83 NGOs from 35 countries, is also working to restrict the use of microplastics. Organizations in Korea like Korea's Women's Environmental Solidarity (KWEN) and the East Asian Community Ocean (OSEAN) are also involved in the movement.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the effect of microplastics on humans has not yet been disclosed, but the impact on the environment must be dealt with by industry and nations for the sake of future generations. Thus, the microplastics problem should be considered a serious problem by global community and they need to start looking into the impact on human bodies and possible related sicknesses. Our lives and those of future generation could be at stake.

심형석, Edward Ng, 김민, 박근후 dankookherald@gmail.com

![[Campus Magnifier] Let's Surf the Library!](/news/photo/202404/12496_1765_4143.jpg) [Campus Magnifier] Let's Surf the Library!

[Campus Magnifier] Let's Surf the Library!

![[Campus Magnifier] Let's Surf the Library!](/news/thumbnail/202404/12496_1765_4143_v150.jpg)