Hearing the news about the death of scenario writer due to the hardships of life and the death of a North Korean mother and son defector makes you wonder how this could happen in Korea in 2011 and 2019, the twenty-first century. They were all sacrificed due to our ‘welfare blind spots’. Blind spots in the welfare system lead some families or individuals to live under unnecessary stress and hardship often resulting in fatal consequences.

The problem has resurfaced in the public eye yet again when on September 5, 2020, a mother and daughter were discovered dead in their home in Changwon. They died and their badly decomposed bodies were only discovered 20 days. It was found that the mother died first leaving her young daughter alone to starve to death. The daughter had been living in state custody since 2011 when she was 13 years old as her mother was accused of child abuse for leaving her alone at home unattended. In 2017 she was forced to leave the state care because she was 20 years old, but the authorities thought she was not ready to live by herself and opted to keep her longer. By 2018 the mother encouraged her daughter to return to live with her and left the facility willingly to the care of her mother. However, her mom was diagnosed schizophrenia in 2011. The daughter was an undiagnosed schizophrenic, but she also showed symptoms of a borderline personality disorder and autism while being held in welfare facilities. She had a grade 5 to 6 degree disability. However, neither the mother nor the daughter were registered as disabled, so they did not belong to a vulnerable community group and receive the associated welfare benefits.

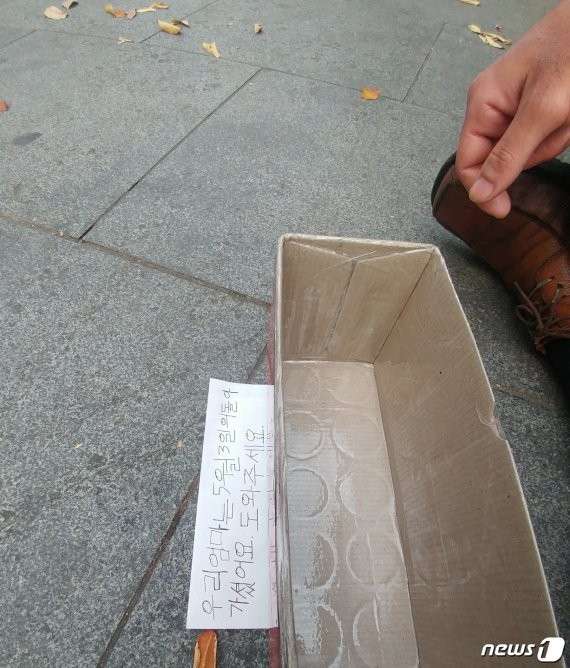

Last December, a woman in her 60s was discovered 5 months after her death in Bangbae-dong, Seoul. She was a recipient of basic living wage for over 10 years and lived with her son. After her death, her son who had developmental disability, went out to the subway asking for help with a box covered in clumsy handwriting. However, for over a month, nobody helped him. A social worker eventually reported the incident to the police after learning his mother had passed away. The problem was they could not receive proper medical care. Under the current law, she had to contact her divorced husband to receive consent for an income investigation to get a living wage adjustment. She was extremely reluctant to contact her daughter and her former husband. To further complicate the matter, her son was not registered as disabled, so he did not qualify for welfare benefits. To register as being developmentally disabled, the mother would have had to take her son in for 6 months of examination and treatment, a process too costly for them to afford.

|

| ▲ Choi, a developmentally disabled man, is asking for help in front of Isu Station. (Photo from Newsone) |

The government defines the scope of the vulnerable as those who have difficulty purchasing necessary social services at market prices or who have trouble getting a job under normal conditions in the labor market. The vulnerable class includes a variety of protection targets, including the elderly, the disabled, North Korean defectors, people with rare incurable diseases, and foreign workers. They are protected by the Employment Promotion and Vocational Rehabilitation Act for the Disabled, the Single-Parent Family Support Act, the Criminal Victims Protection Act, and the Framework Act on the Treatment of Foreigners in Korea. Single-parent families can receive support if the Minister of Gender Equality and Family agrees they meet the legislated criteria. They consider minimum living costs, income level, and the property level of the protected person on a yearly basis. Foreigners living in Korea who have married or are in a marriage relationship with a Korean can also receive support. Victims of domestic violence are also protected under the Crime Victim Protection Act as they are included in the category of vulnerable people. The Ministry is providing them with consultation, legal and medical services, so they can prepare to lead a more independent life.

According to the Korean Institute for Health and Social Affairs' report, ‘Comparison of Welfare Service Providers' perceptions of blind spots and fraudulent supply and demand in the welfare sector’ account for more than 40% of the problems. The report concludes, they have "many blind spots." Local government officials in charge of welfare pointed to ‘public aid, a national basic living security system, or basic pension amount,’ as the policy program with the most serious concerns among the social security systems currently in effect. In particular, the program that has the most serious blind spots in the national basic living security system, a representative welfare system of public assistance, including the ‘Living Benefit’ (49.0%) followed by the ‘Housing Benefit’ (25.7%) and ‘Medical Care’ (21.4%). These three programs have one thing in common. All of them apply a criterion for family support obligations, preventing families with assets or incomes above a certain level, such as parents and children, from being paid even if their property or income meets the criteria for selecting beneficiaries. It is this provision that hindered the availability of medical benefits in the Bangbae-dong case and is considered a major cause of blind spots in welfare. The survey also revealed that 45.7% of the local welfare officers who responded believed "the target did not apply" as the reason for the overall blind spot in the welfare system. It was followed by "structural exclusion due to selective application" (36.4%) and "because the level of welfare service or salary is too low as compared to the needs of the target" (15.7%).

|

| ▲ Current status of people receiving national basic livelihood security program (Photo from Hankookilbo) |

A lot of effort has been made to eliminate blind spots in our social services system. Current and former administrations did try to solve the problem. Following the death of a screen writer in her 30s, distressed from hardship of life in 2011, the Lee Myung-bak administration increased the welfare budget exponentially as a countermeasure. However, three years later, another incident in which a mother and her three daughters committed suicide because they were forced to live on 700,000 won a month for rent and bills. Distressed from hardships of life they chose to end theirs. The Park Geun-hye administration responded by loosening the strict eligibility standards and set up system to identify households at welfare risks by amending National Basic Livelihood Security Act, Emergency Aid and Support Act and enacting the Act on the Use and Provision of Social Security Benefits and Search for Eligible Beneficiaries. Despite these efforts, similar incidents keep resurfacing. A mother and her daughter, living in Jeungpyeong, committed suicide due to economic hardships in 2018 and a mother and her son from North Korea were found starved to death in 2019.

Professor Jeong Chang-nyul in the Department of Public Administration at Dankook University (DKU) said that it is exceedingly difficult to eliminate all welfare blind spots. Though policies and measures to identify households at welfare risk exist, it is hard to check up on every single person’s financial conditions and whether he or she is taking advantage of all the welfare benefits they are qualified to receive. The professor said, “Korea isn’t the only country with a welfare blind spot problem. No matter what kind of welfare benefit one wants to get including national pension, housing benefits and livelihood benefits, people must apply for it and some people refuse to do this. The take-up rate of public aid, which shows the percentage of eligible people who accept government assistance, is 60-70% in most countries.” He continued, “One of the biggest reasons for a low take-up rate is the ‘stigma’ attached to receiving financial aid. People equate welfare benefits as being ‘government certified poor’.”

He suggested 3 different solutions. First, eligible beneficiaries need to understand that accepting public aid is nothing to be ashamed of. It is their right. He also said that beneficiaries feel stigmatized when they must disclose personal information including bank accounts. He believes there should be an alternative system in place that simplifies the process or even eliminates such stages. The last suggestion he made was to improve the system that matches eligible beneficiaries with welfare benefits. According to the 2016-2019 welfare blind spot identification system data by the Korean Social Security Information Service, about 200,000 people were found in welfare blind spot, however only 40% of them were eventually connected to welfare services. He cited the case of the mother and son in Bangbae-dong’ as one of those cases. He said a better review process will help prevent the recurrence of similar incidents.

The professor added, “Students can also help solve the problem of welfare blind spots. Dankookians (Students of DKU) have chances to meet vulnerable people through volunteer activities including youth mentoring programs. Listening to their stories and checking if they have a desire for welfare assistance or advising them of the welfare benefits available would be helpful. If you do not have the information necessary to help them, being proactive by visiting a local community center or institution for additional resources would be great help to solve the problem.” He stressed that we should think of welfare benefits as a measure to keep all of our communities healthy, not just helping the poor.

The Covid-19 pandemic has worsened the financial conditions and further alienated the already vulnerable class. Along with the welfare system, understanding its benefits for society as a whole and paying constant attention to the well-being of our neighbors are critical now, more than ever. Students may not be able to revise the welfare system, but they can make an effort to look after their communities and help reduce our welfare blind spots.

김서연, 구시현, 정소연 dankookherald@gmail.com

Vote for the Campus Brand Naming!

Vote for the Campus Brand Naming!

![[Campus Magnifier] Let's Surf the Library!](/news/thumbnail/202404/12496_1765_4143_v150.jpg)